Thank you for explaining this. It helps a lot.

Though what I gather from this is that there are even more copies of my text to be aware of:

- one local copy, outside of git

- the upstream copy (which may also be stored locally or remotely or both)

- the main branch/ origin, into which my upstream copy will eventually be merged.

- add multiple upstream branches to that and

While I understand the benefit of having a lot of copies, it also means that you need to be aware of, which copy to work on at any point in time (or when doing particular tasks). I think this comes a bit more naturally when writing code, especially in a team, but it’s not how most people go about writing texts (articles, books, …). Even without git, I sometimes fine myself scratching my head when I return to a writing projects after some weeks of interruption and can’t remember what the file was called or whether I wrote it in Word or in LaTeX or what. - I’m not expecting anyone to solve this stupidity of mine. I’m just saying that git might add more of that kind of friction…

(Although I suspect that once you have wrapped your head around how git works or developed a routine of how to work with it, it might well make my stupidity less of a problem.)

And that may or may not be a benefit. Before I used more or less all my notes onto the computer, I hade so many paper snippets and scribbles all over the place that I couldn’t find a note when I needed it (or wondered whether I actually wrote it down or just had the idea).

The reason I like writing in LaTeX (or Markdown) is that it makes it super easy to comment out some parts or write notes to your future self while being able to produce a clean version of the document at any time. I think a lot of the different versions of a text that git could take care of are actually in my main document all the time, just some of them are commented out and therefore invisible in the output document.

What an ingenious idea! Why did I never come up with that? I love it. This also works in LaTeX and it should indeed make the use of diff/git a bit easier.

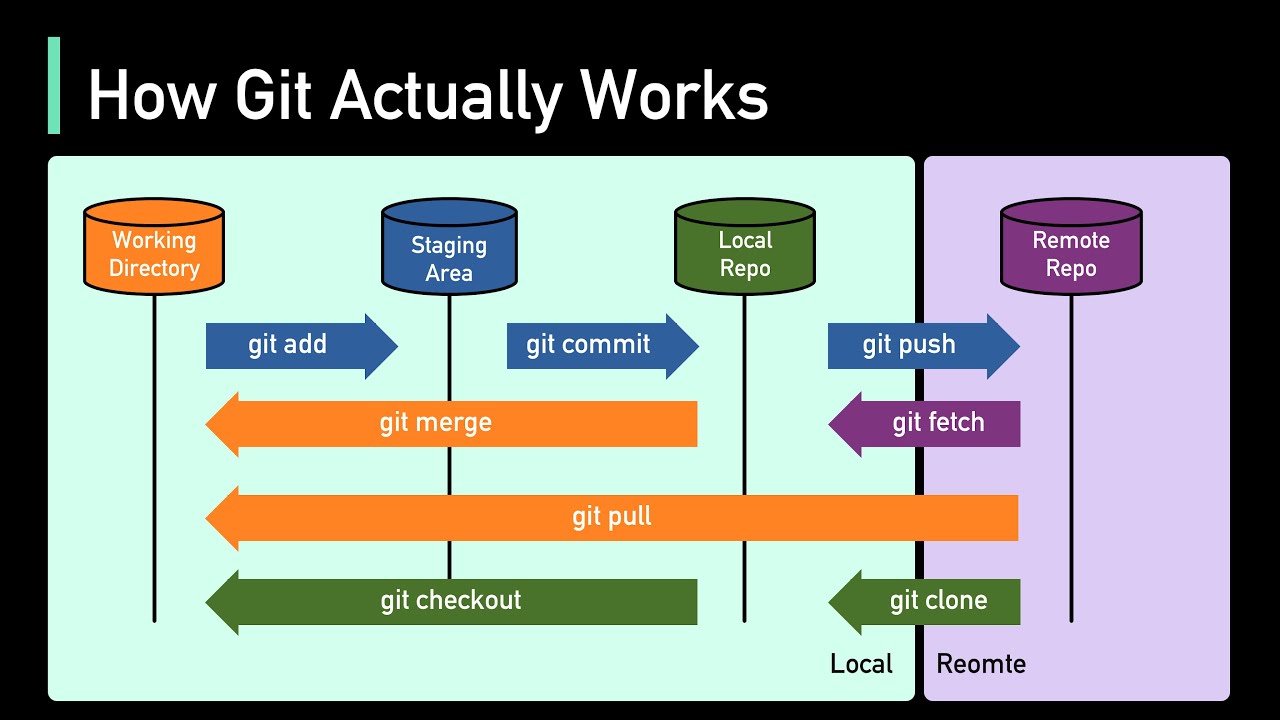

I found this quick video helpful to get a basic understanding of the different places where versions are stored:

And in this one, someone shows how they used git to write a book. It really helps to get a better understanding of what you can do, like using committ messages for documenting progress/ direction or using branches for chapters (though I’m not exactly sure what the benefits of the latter are):

(Note, however, that the Kanban Board feature in GitKraken has been discontinued)